Seizures and Epilepsy

- related: Neurology

- tags: #neurology

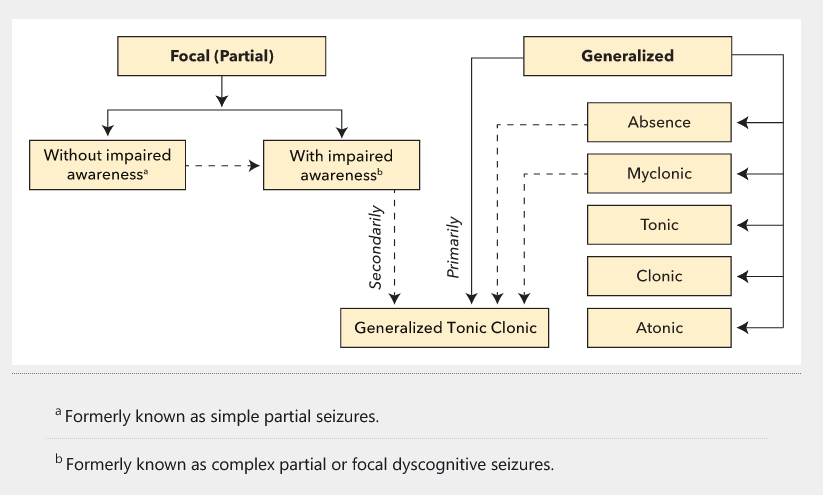

Clinical Presentation of Seizures

Epilepsy is defined as at least two unprovoked seizures more than 24 hours apart, or one unprovoked seizure with a risk of further seizures that is similar to the risk after two unprovoked seizures (at least 60%). The term “epileptic seizure” does not imply that the seizure is related to epilepsy; rather, it means that the seizure is “real”—that is, secondary to abnormal electrical activity in the brain and not to some other cause (such as syncope or psychiatric disease). The diagnosis of an epileptic seizure relies on a detailed patient history. The stereotyped nature of clinical events is characteristic of seizures; symptom variability from event to event suggests an alternative diagnosis. Epilepsy usually requires antiepileptic drug (AED) therapy, but isolated seizures may not, especially if provoked by reversible or preventable causes. The terminology of seizures is evolving, with more descriptive terms suggested as replacements for “simple partial seizures” and “complex partial seizures” (Figure 4).

Common seizure types based on International League Against Epilepsy classification. The dashed arrows represent the possibility of one seizure type transitioning directly into another when a patient is seizing. Note that generalized tonic clonic seizures may start out focal or generalized.

Common seizure types based on International League Against Epilepsy classification. The dashed arrows represent the possibility of one seizure type transitioning directly into another when a patient is seizing. Note that generalized tonic clonic seizures may start out focal or generalized.

- Generalized affect both sides of the brain at the same time.

- Focal affect one area or side of the brain.

Focal Seizures

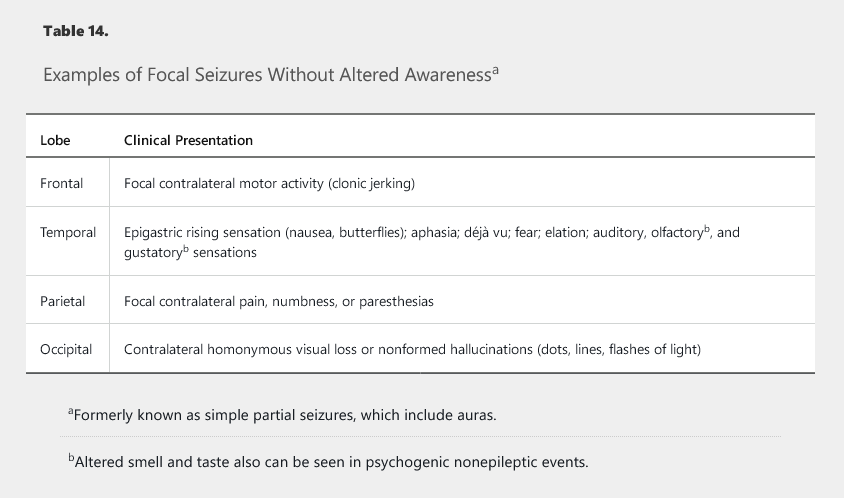

Focal seizures may occur without alteration of awareness (formerly, simple partial seizures) or with alteration of awareness (formerly, complex partial seizures). The first type includes auras, which are not just warning symptoms but actually very localized focal seizures (Table 14). Seizures involving impaired awareness may affect memory, responsiveness, language, or cognition. Both focal seizures and generalized absence seizures can present as “staring episodes” and must be carefully differentiated (Table 15).

Patients may not remember or volunteer a history of focal seizures because they may be unaware of the events. Therefore, it is important to ask about discrete episodes of memory loss or time lapses. A typical temporal lobe seizure, for example, may start with an aura of a rising feeling in the stomach, déjà vu, or fear, followed by altered awareness with staring, arrest of speech or behavior, and semipurposeful repetitive movements, called automatisms. Focal seizures also may present with autonomic symptoms, such as palpitations, sweating, and hot flashes. Whereas these symptoms also can be seen with psychiatric and cardiac disorders, focal seizures will typically have sudden onset, stereotyped symptoms, and a short duration.

Generalized Seizures

Generalized tonic-clonic seizures (GTCS) have a characteristic pattern of tonic activity followed by clonic activity. During the tonic phase, eyes are wide open while the entire body stiffens, and typically there is a single loud groan or “ictal cry” (not actual crying or sobbing). During the clonic phase, rhythmic jerking occurs synchronously in all limbs, initially at high frequency, with eventual slowing and cessation. This movement often is followed by stertor (deep, slow snoring). A postictal state with confusion, hypersomnolence, and fatigue is common and can persist for hours or even a day.

GTCS may be generalized at onset and are considered to be primarily generalized seizures. These may be preceded by other generalized events, such as absence or myoclonic seizures. Alternatively, GTCS may start as focal seizures with subsequent spread to both hemispheres (secondarily generalized). Aura or automatisms before GTCS and postictal unilateral weakness (Todd paralysis) suggest a focal onset.

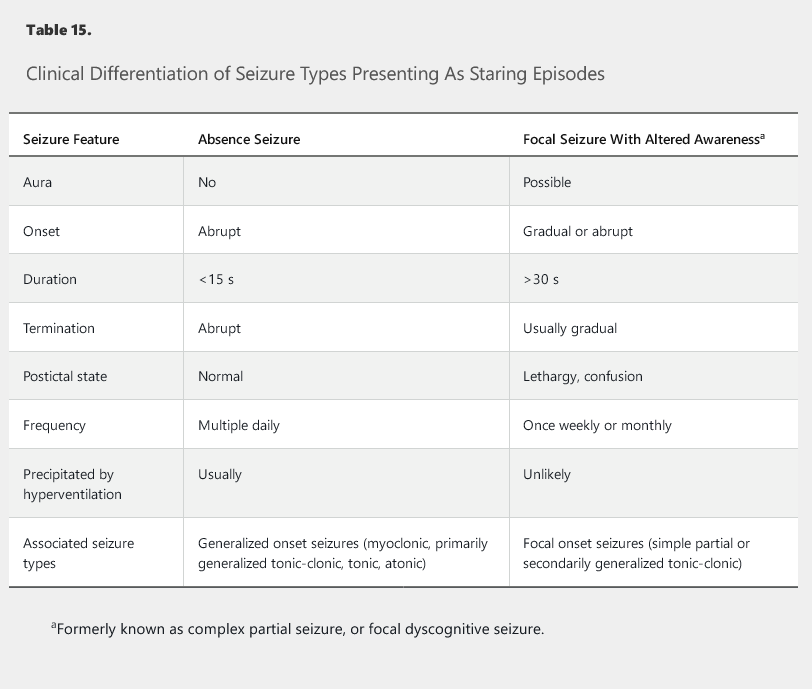

Absence seizures are characterized by brief episodes of staring. Many patients are unaware of these seizures. They may occur as the only seizure type in school-age children and are often confused with attention deficit disorder. In adulthood, absence seizures most often occur in combination with other generalized seizure types, such as GTCS or myoclonic seizures.

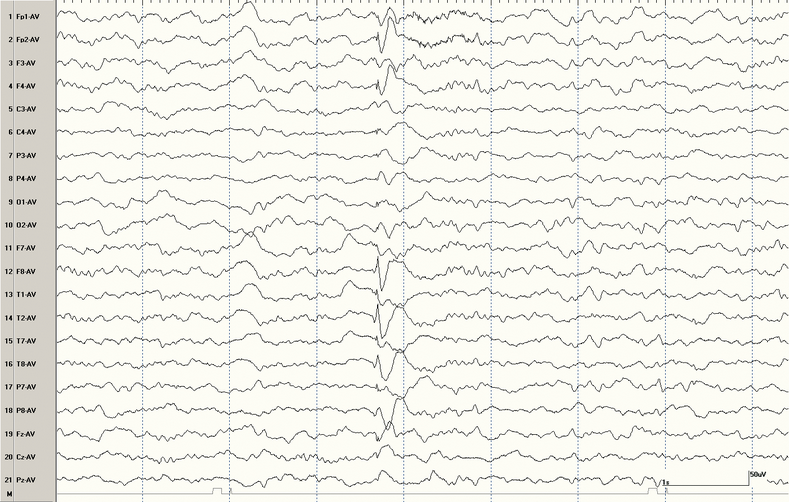

Myoclonus is a single quick jerk of a limb or the entire body lasting less than a second and is not always associated with a seizure (see Movement Disorders). A diagnosis of myoclonic seizures can be confirmed by electroencephalography (EEG), with each jerk associated with a generalized spike-and-wave discharge (Figure 5). Myoclonic seizures also can occur repetitively and result in falls. Awareness is maintained and duration is very short (<1 second), which differentiates myoclonic seizures from GTCS.

Electroencephalogram showing generalized spike-and-wave discharges. In an appropriate clinical setting, this strongly supports a diagnosis of generalized epilepsy.

Electroencephalogram showing generalized spike-and-wave discharges. In an appropriate clinical setting, this strongly supports a diagnosis of generalized epilepsy.

Tonic seizures present as episodes of increased muscle tone, ranging from mild extension of the arms and head to a more severe stiffening of the entire body. Atonic seizures present with sudden loss of muscle tone. Both tonic and atonic seizures occur with no warning, last a few seconds, and cause altered awareness, which often leads to falls and physical injuries; they lack postevent confusion. Prolonged episodes of increased or decreased tone with long duration of loss of consciousness are unlikely to represent seizures.

Epilepsy Syndromes

Focal Epilepsies

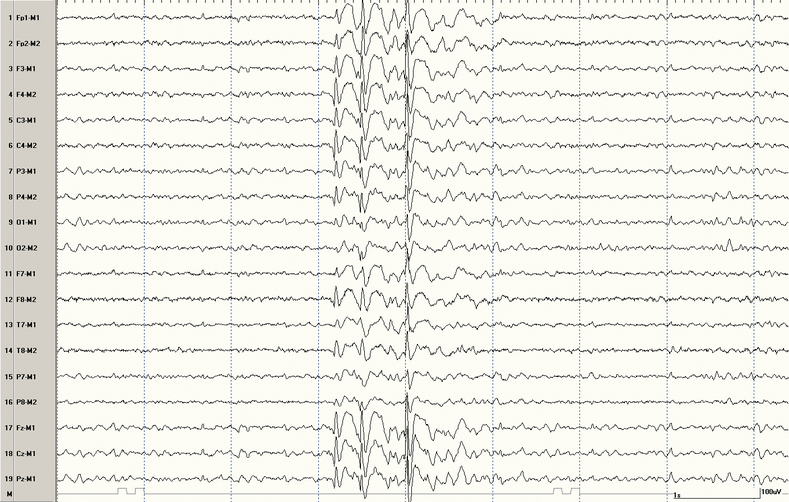

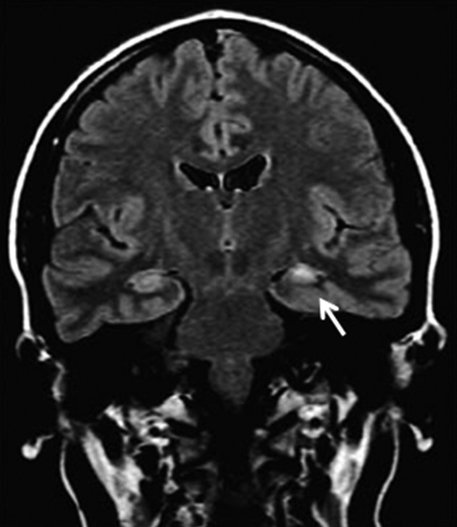

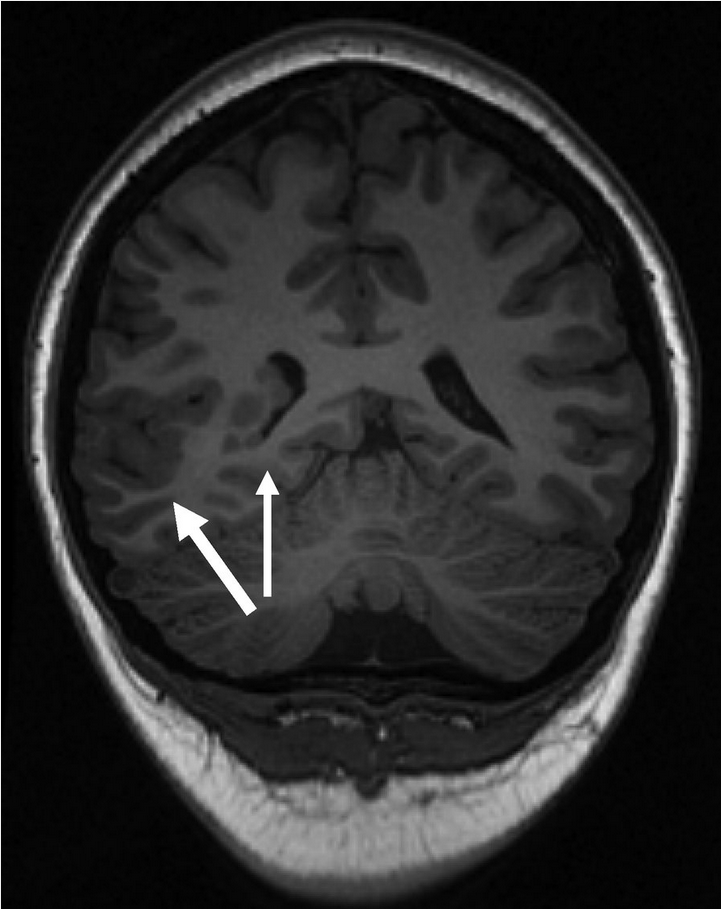

Identifiable causes of focal epilepsies include structural lesions, such as mesial temporal sclerosis, cavernous malformations, cortical dysplasia, traumatic brain injury, stroke, and tumors, all of which may be seen on MRI (Figure 6 and Figure 7). EEG may show focal spikes or sharp waves in the appropriate brain region (Figure 8). In most adults with focal epilepsy, however, brain MRI is normal and the cause is unknown.

Mesial temporal sclerosis. The coronal fluid-attenuated inversion recovery MRI shows increased signal intensity and atrophy of the left mesial temporal lobe (arrow).

Mesial temporal sclerosis. The coronal fluid-attenuated inversion recovery MRI shows increased signal intensity and atrophy of the left mesial temporal lobe (arrow).

Focal cortical dysplasia with periventricular nodular heterotopia. Coronal MRI showing a focal area of thickened cortex in the right temporal region (thick arrow) and nodules of abnormal neuronal tissue along the ventricular surface (thin arrow).

Focal cortical dysplasia with periventricular nodular heterotopia. Coronal MRI showing a focal area of thickened cortex in the right temporal region (thick arrow) and nodules of abnormal neuronal tissue along the ventricular surface (thin arrow).

Electroencephalogram showing focal (left temporal) sharp waves. In an appropriate clinical setting, this strongly supports a diagnosis of temporal lobe epilepsy.

Electroencephalogram showing focal (left temporal) sharp waves. In an appropriate clinical setting, this strongly supports a diagnosis of temporal lobe epilepsy.

Temporal lobe epilepsy is the most common adult-onset focal epilepsy. Typical symptoms include aura, loss of awareness, staring, behavior arrest, and amnesia. Automatisms, repetitive semipurposeful movements (such as lip smacking, chewing, and swallowing), and picking or grabbing movements with the ipsilateral arm are common. Speech arrest may be seen with involvement of the dominant hemisphere.

Mesial temporal sclerosis with hippocampal atrophy is the most common cause of medication-resistant adult-onset focal epilepsy.

Idiopathic (Genetic) Generalized Epilepsies

Idiopathic epilepsy is “pure” epilepsy without an underlying neurologic disorder. Newer classification schemes call this type of epilepsy “genetic,” even in the absence of a positive family history, inheritability, or a single identifiable gene. In adults, juvenile myoclonic epilepsy (JME) is the most common form of idiopathic generalized epilepsy. JME seizures often are called “college seizures” because of the age of onset (teens or twenties) and associated triggers (sleep deprivation, alcohol use, and stress). Epilepsy may not be diagnosed until the first GTCS occurs because myoclonic seizures often remain unrecognized by patients, family, or friends until a physician takes a careful and complete history.

The presence of myoclonic seizures is required for the diagnosis of JME; patients may report dropping items from their hands, commonly a coffee cup or hairbrush, because myoclonic seizures in JME generally occur in the morning. Most affected patients have GTCS, and approximately 30% of patients have absence seizures. Patients are usually otherwise neurologically healthy and can live relatively normal lives because seizures are often controlled with one or two AEDs. Brain MRI is typically normal, and EEG may show generalized spike-and-wave discharges (see Figure 5). Lifelong AED therapy is typically required.

Diagnostic Evaluation of Seizures and Epilepsy

Initial Approach to the Patient With a First Seizure

For any patient with a first seizure, obtaining a detailed history is crucial to distinguish seizures from other causes of symptoms. The distinction between seizure and nonseizure events and clarification of first-time versus recurrent episodes are key. A history of previous staring events or myoclonus may help identify patients with epilepsy and should be specifically sought out through careful questioning.

Differential Diagnosis of Seizures

Many episodic disorders mimic seizures but are nonepileptic events. These include syncope, migraine, movement disorders (tremor, tics), sleep disorders, stroke, and psychogenic events. Seizures usually have positive symptoms, such as jerking, tingling, and visual flashes, whereas strokes have negative symptoms, such as weakness, numbness, and loss of vision. Normal mentation with a headache after the episode suggests migraine. Occurrence only in public suggests panic disorder with agoraphobia.

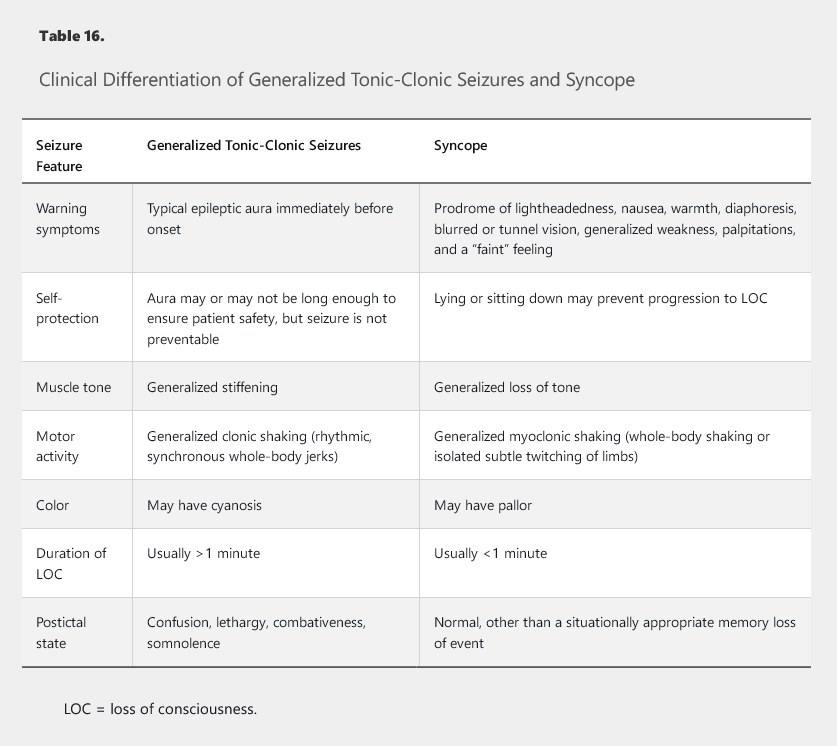

Associated lightheadedness or chest pain may suggest syncope or cardiac disease. Syncope often presents with shaking (“convulsive syncope”) and must be differentiated from GTCS (Table 16). In one study, more than 90% of healthy volunteers had nonepileptic myoclonus (generalized or multifocal) when syncope was induced; only a minority had classic, motionless syncope. For distinguishing seizures from syncope and psychogenic loss of consciousness, video EEG can be very useful, in combination with tilt-table testing, because it can specifically differentiate these events.

Psychogenic Nonepileptic Spells/Events

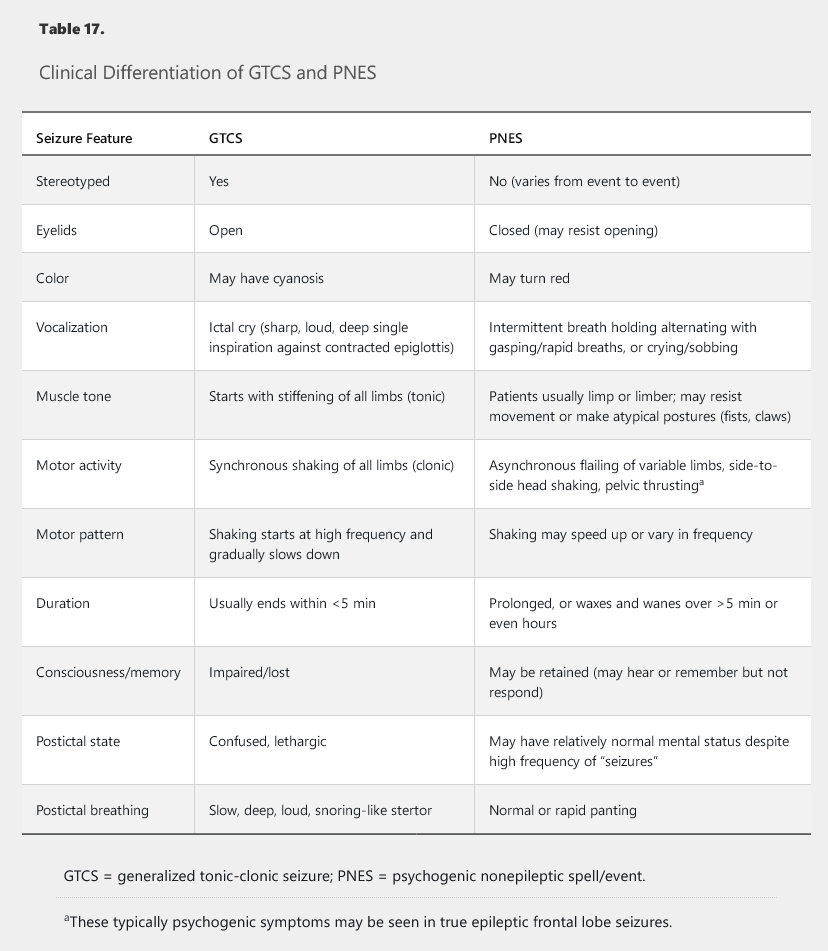

Psychogenic nonepileptic spells/events (PNES) were formerly called pseudoseizures or psychogenic nonepileptic seizures. These latter terms should be avoided because seizure is a misnomer in this context, and “pseudo” implies falseness of the symptoms. PNES are most often related to posttraumatic stress disorder or conversion disorder. Factitious disorder and malingering are rare. Patients often have a history of military combat, sexual or physical abuse, chronic medical illness, or prominent life stressors. PNES often mimic GTCS, but certain features help distinguish the diagnoses (Table 17). Event capture during video EEG monitoring usually is required to confirm the diagnosis.

Diagnostic Evaluation

Neuroimaging is recommended for all patients with a first seizure. CT of the head is adequate initially to rapidly exclude emergent pathology, including hemorrhage, but MRI is required in most patients. Contrast-enhanced CT or MRI may be deferred unless infection, tumor, or vascular lesions are suspected. Because temporal lobe epilepsy is common, MRI sequences focusing on the hippocampus and temporal lobes are useful (coronal T2-weighted, fluid-attenuated inversion recovery, and thin-slice T1-weighted imaging). Functional imaging (PET and single-photon emission CT) is considered when planning for epilepsy surgery but is not routinely indicated.

Outpatient EEG also is recommended in patients with a first seizure. Because capture of an actual seizure is unlikely, the physician must rely on “epileptiform” abnormalities, such as focal sharp waves (see Figure 8) or generalized spike-and-wave discharges (see Figure 5). These findings are considered relatively specific for epilepsy; although not diagnostic, they may help support the diagnosis in an appropriate clinical context. A single routine EEG is only 40% to 50% sensitive for such findings, but the yield can increase to 80% to 90% with repeated studies, prolonged studies, and studies that capture sleep.

MRI and EEG can be performed at a follow-up evaluation, but the yield of EEG is higher within 24 hours of GTCS. Emergent lumbar puncture is recommended in adults only if an infectious cause, such as meningitis or encephalitis, is suspected.

Epilepsy Monitoring Units

A normal EEG does not rule out epilepsy. Capturing events during continuous 24-hour video EEG monitoring is the gold standard in diagnosis. Continuous video EEG monitoring is performed in an epilepsy-monitoring unit during a multiple-day elective hospitalization during which AEDs are decreased or withdrawn under close supervision. Patients who have not responded to two adequately dosed AEDs are considered to have refractory disease (see Intractable Epilepsy and Epilepsy Surgery) and also should be referred to an epilepsy center, where evaluation in an epilepsy-monitoring unit can both confirm the diagnosis of epilepsy and determine candidacy for epilepsy surgery.

Other Continuous Electroencephalographic Monitoring

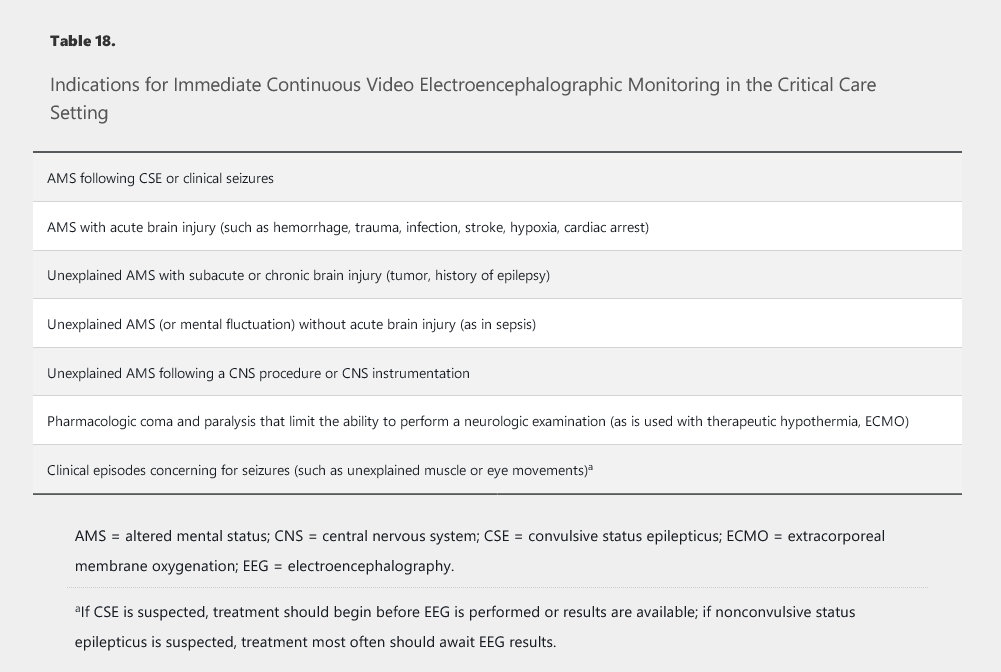

Continuous video EEG monitoring also is useful in the ICU (Table 18). It can determine if episodic events are truly seizures, particularly in sedated or confused patients who cannot provide a history. This type of EEG additionally is the only method of diagnosing nonconvulsive status epilepticus.

Provoked, Unprovoked, and Triggered Seizures

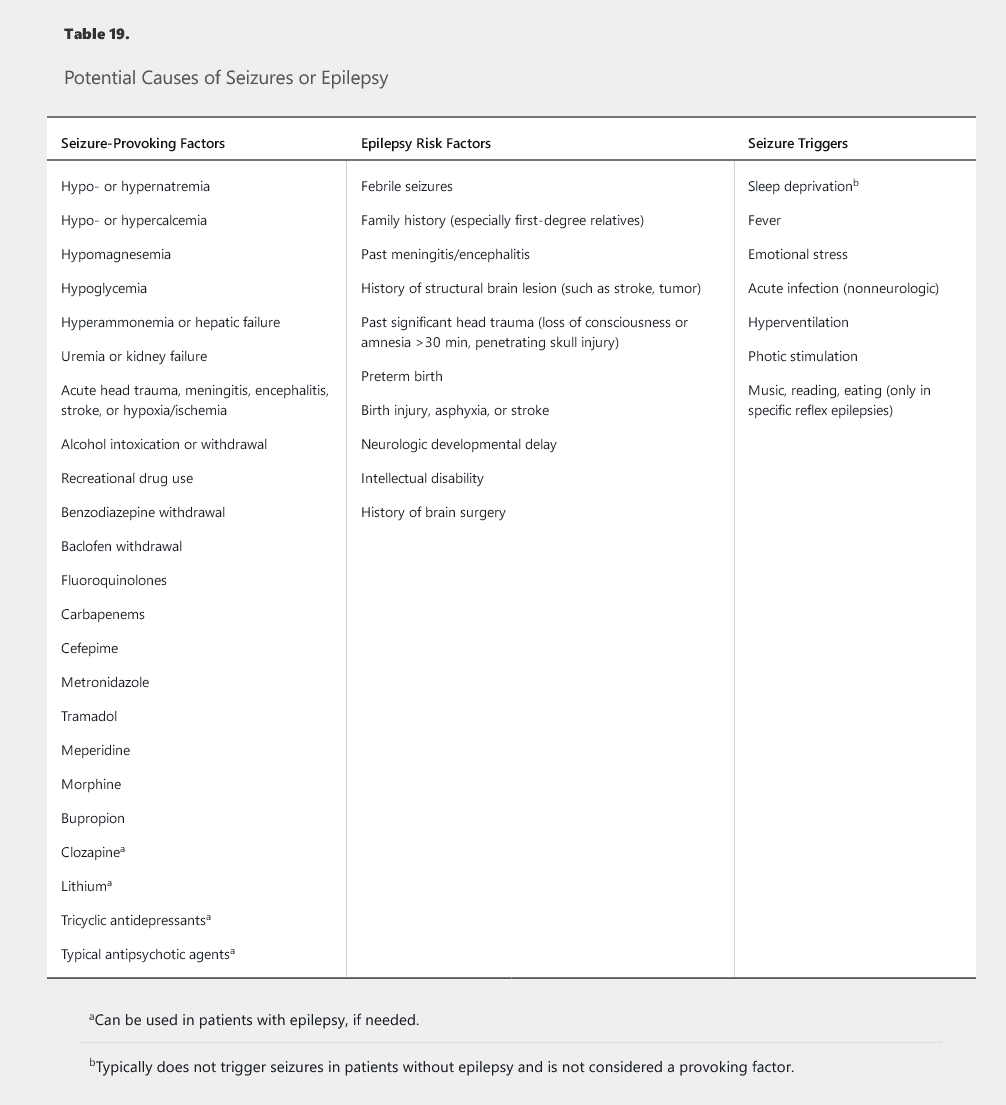

Provoking factors, risk factors, and triggers all can all lead to seizures (Table 19), and differentiating among them is essential. Provoking factors can cause seizures in patients with or without epilepsy; avoidance of these provocations should prevent further seizures. Particular attention should be paid to the patient's medications, and drugs that can cause a seizure or lower seizure threshold (such as tramadol, meperidine, bupropion, fluoroquinolones, carbapenems, and cefepime) should be avoided. Risk factors increase the chance of developing epilepsy later in life; however, an acute symptomatic seizure (such as a seizure occurring in the first week after traumatic brain injury, stroke, or meningitis) may not necessarily lead to the development of epilepsy. Although triggers lead to seizures in patients with epilepsy, they are not the cause of epilepsy (and are not considered provoking factors).

Determining the risk of recurrence guides the decision to treat. The 2-year recurrence risk after a single unprovoked seizure is approximately 40%. Risk is lower (20%-30%) if there are no epilepsy risk factors and the MRI and EEG are normal. A first unprovoked seizure is often not treated; although treatment may reduce the risk of seizure over the next 2 years, it does not change a patient's long-term prognosis for developing epilepsy. In the setting of two unprovoked seizures or one unprovoked seizure with significant EEG or MRI abnormalities, recurrence risk is at least 60%, and treatment is recommended.

Treatment of Epilepsy

Antiepileptic Drug Therapy

Empiric pharmacologic treatment generally is not recommended unless the patient's history is strongly suggestive of seizures or epilepsy. The exception is convulsive status epilepticus, which must be treated emergently if clinically suspected. Similarly, prophylactic treatment is avoided except in specific situations, such as during the week after severe head trauma or brain tumor resection. Alcohol- or benzodiazepine-withdrawal seizures typically are not treated with AEDs.

In general, neurologists do not treat with an antiepileptic drug (AED) unless the patient has had > 2 unprovoked seizures separated by more than 24 hours. In this patient, the seizure was provoked by an underlying structural lesion in the brain. Therefore, treatment with an AED is indicated as the risk of seizure recurrence is high. Given that this patient is of reproductive age, lamotrigine alone or levetiracetam is the best AED to start as it has the fewest teratogenic side effects. Valproic acid is generally contraindicated in young women of reproductive age due to potential teratogenic effects.

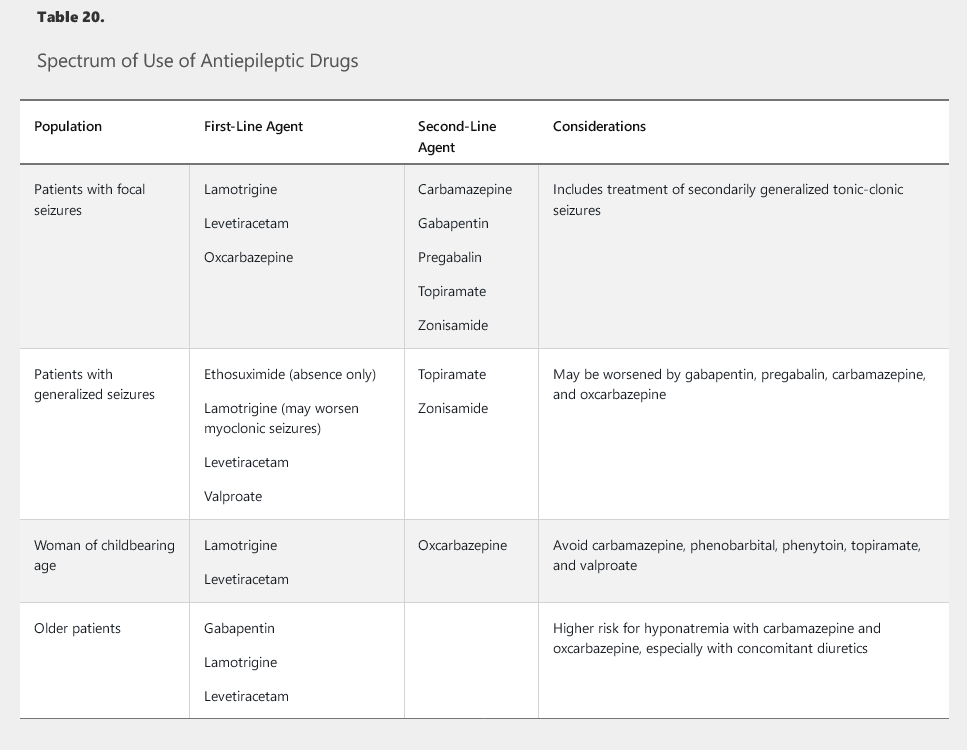

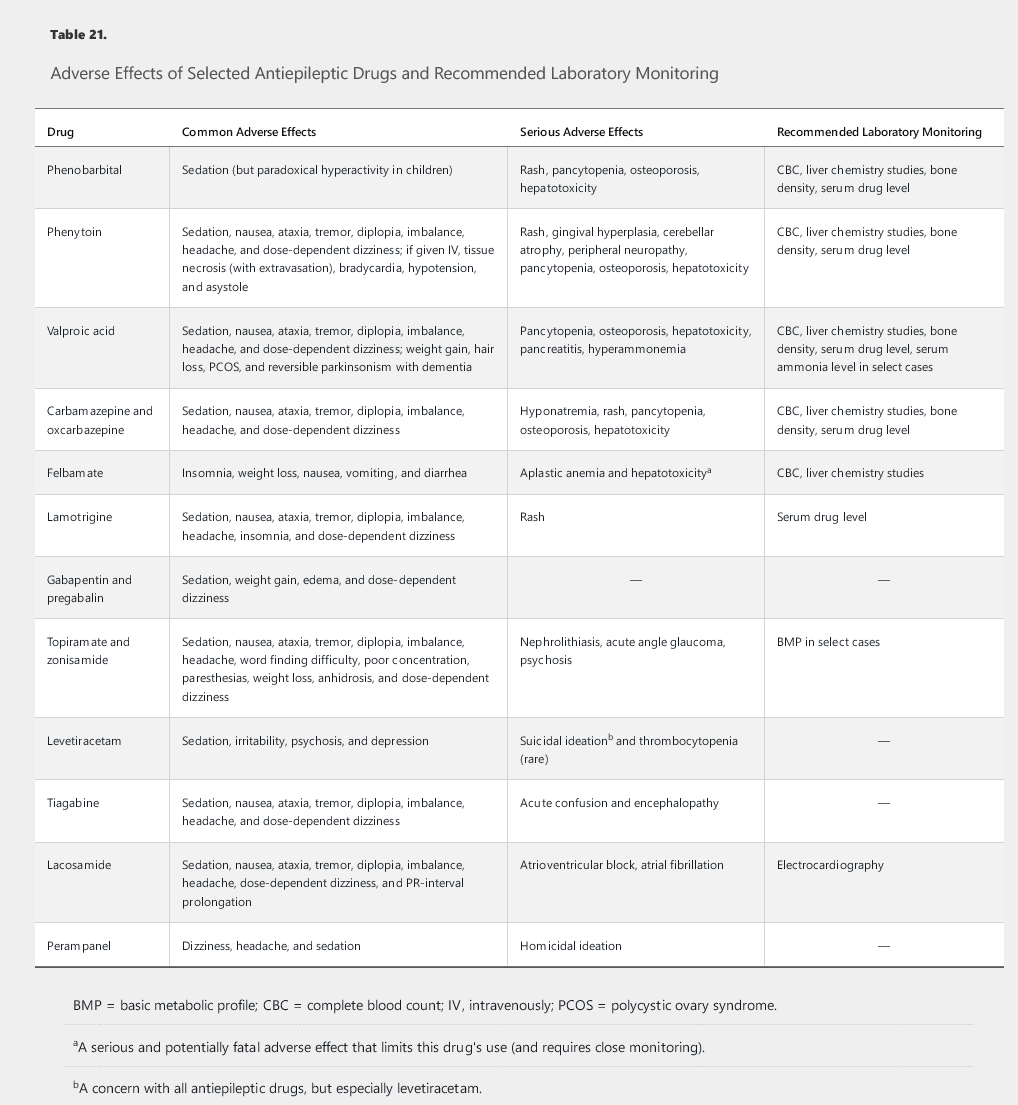

Selection and Adverse Effects of Antiepileptic Drugs

Many AEDs are available for patients with epilepsy (Table 20). Newer AEDs, although not more effective in controlling seizures than older AEDs, are often preferred because they have fewer adverse effects, fewer drug interactions, and a reduced need for laboratory monitoring. The higher cost and shorter length of experience with the newer AEDs are disadvantages. Most often, treatment is guided by the seizure type rather than AED mechanism or epilepsy cause. When a patient has GTCS and focal onset is not certain, a broad-spectrum AED should be used. Focal seizure medications are also used for secondarily generalized seizures.

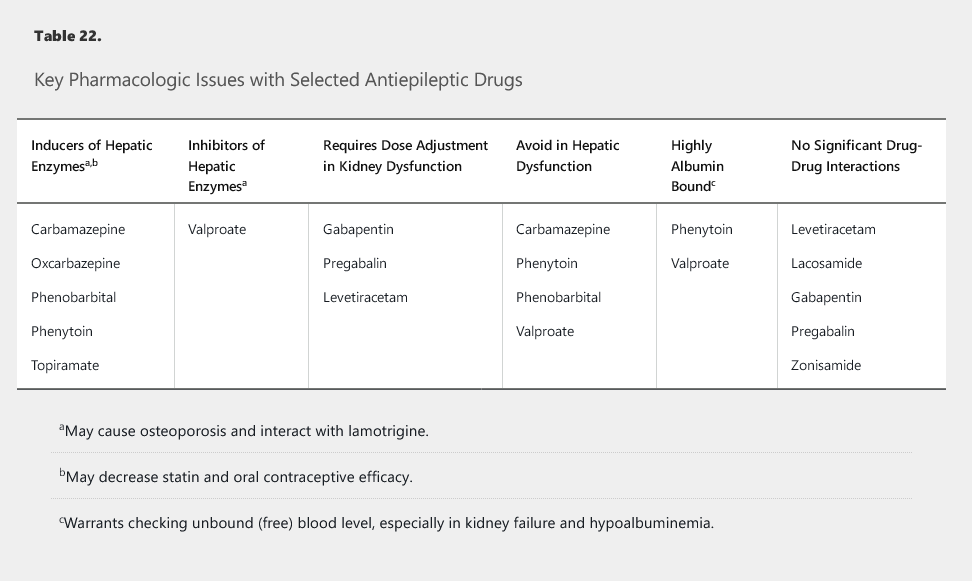

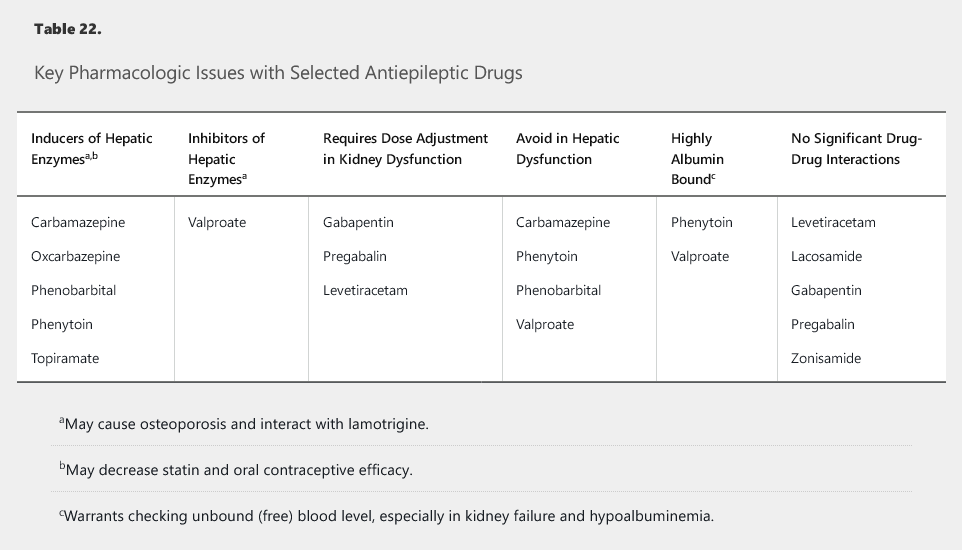

Most dangerous AED toxicities (rash, pancytopenia, hepatotoxicity) are idiosyncratic and not necessarily dose related. Table 21 lists common adverse effects and laboratory monitoring recommendations. Key dose-dependent adverse effects include oxcarbazepine-related hyponatremia and valproic acid–related thrombocytopenia. Hyponatremia is a particular concern with oxcarbazepine and carbamazepine in older patients, especially with concomitant diuretic use. Enzyme-inducing AEDs (Table 22) increase statin clearance and necessitate higher doses or alternative options; they also can increase bone catabolism. Therefore, bone density testing and supplementation of calcium and vitamin D are recommended with enzyme-inducing AEDs (and with valproic acid).

Phenytoin, carbamazepine, phenobarbital, and lamotrigine are AEDs that commonly cause rash, which usually resolves with discontinuation of the drug. AED-related rashes, however, are sometimes severe and life-threatening. For example, rapid titration of lamotrigine has been associated with the development of Stevens-Johnson syndrome, toxic epidermal necrolysis, and drug reaction with eosinophilia and systemic symptoms. These AEDs also should be avoided in patients of Asian heritage unless testing for genetic predisposition (presence of HLA-B*1502 allele) is negative. Nevertheless, lamotrigine is one of the most safe and effective AEDs used today, when titrated slowly.

All AEDs carry a warning about worsening depression and suicidality, and all patients must be screened and monitored for these symptoms. Levetiracetam may cause depression, anxiety, anger, or agitation. Perampanel may cause homicidal ideation. Topiramate may cause psychosis. Lamotrigine and valproic acid, on the other hand, are known to be mood stabilizing.

Monitoring and Discontinuing Antiepileptic Drugs

Measuring serum levels of certain AEDs (phenytoin, carbamazepine, valproic acid, phenobarbital, oxcarbazepine, lamotrigine) is useful, given their known therapeutic windows and predictable dose-related adverse effects. However, in a patient whose epilepsy is well-controlled without clinical adverse effects, dose reduction because of high levels usually is not warranted.

Generic AEDs are appropriate for most patients, given recent guidelines. Well-designed studies have not shown differences in AED bioequivalence (on the basis of FDA standards) when switching between generic drugs or switching from a brand to a generic drug for patients with epilepsy. Generic substitution reduces cost and does not compromise efficacy. Patients need to be informed of changes in the color and shape of pills.

In addition, phenytoin, carbamazepine, and valproic acid do not have a 1:1 conversion between immediate-release and extended-release formulations. Monitoring for AED toxicity and seizures is advised if a change is made.

Tapering of AEDs can be considered in patients remaining seizure free for at least 2 to 5 years. The best predictor of seizure freedom is time; a prolonged period of seizure freedom predicts further seizure freedom. Factors prohibiting AED weaning include the presence of JME, a history of difficulties in early seizure control, and the presence of significant epilepsy risk factors (see Table 19). Relevant MRI abnormalities, significant EEG abnormalities (especially when not taking AEDs), risk of physical injury, and loss of driving privileges (if unacceptable to the patient) are additional considerations. There are no accepted standards for tapering schedules for AEDs.

Counseling and Lifestyle Adjustments

All patients experiencing a seizure, even a single provoked seizure, must be instructed about seizure precautions, including driving restrictions. Most states restrict driving in patients with any episode of altered awareness or motor control, with the restriction varying by state from 3 to 12 months (see www.epilepsy.com/driving-laws). Additionally, patients should avoid common triggers and provoking factors (see Table 19). Most patients with epilepsy can work, even if they are not completely seizure free. Patients should avoid operating heavy machinery, using firearms, lifting more than 9 kg (20 lb), taking tub baths, swimming in unsupervised locations, and being near open flames or heights (such as rooftops).

Comorbidities and Complications of Epilepsy

Sudden Unexpected Death in Epilepsy Patients

Besides the risk of trauma, asphyxia, and death from a seizure or status epilepticus, epilepsy patients are at risk for unexpected death. This risk is approximately 1 in 1000 and increases to approximately 1 in 100 in patients with intractable seizures, especially those with uncontrolled GTCS and those taking multiple AEDs. Mechanisms are unknown and may involve cardiac, respiratory, and autonomic dysregulation. Studies show that patients prefer to discuss sudden unexpected death in epilepsy openly; doing so can encourage medication adherence and home safety planning (such as using webcams and bed monitors and sharing of bedrooms).

Intractable Epilepsy and Epilepsy Surgery

Any patient who does not achieve seizure freedom for at least 1 year after treatment with two adequately dosed, appropriately chosen AEDs is considered to have medically intractable (drug-resistant) epilepsy and should be referred to an epilepsy center to both confirm the diagnosis and evaluate the patient for surgical candidacy, starting with video EEG monitoring. The chance of achieving seizure control from additional medications (a regimen of three or more AEDs) is less than 10%; therefore, other treatment options must be considered. In appropriately chosen surgical candidates, especially those with temporal lobe epilepsy due to mesial temporal sclerosis, resection can lead to seizure freedom in 60% to 70% of patients. Implantable vagus nerve stimulators and the ketogenic diet are available palliative therapies but do not result in complete seizure control.

Seizures and Epilepsy in Specific Populations

Older Adults

Incidence of new-onset epilepsy is highest in older adults (age > 60 years). Because recurrence after a new-onset seizure in this age group is more likely (50% to 60%) than in younger adults (40%), treatment after one seizure is sometimes considered. Major risk factors for seizure recurrence include stroke and dementia. Older adults usually require lower AED doses and are at increased risk of interactions and decreased drug clearance. Data suggest that levetiracetam, lamotrigine, and gabapentin are better tolerated and no less effective when compared with older AEDs. Valproic acid should be avoided because it can cause (reversible) parkinsonism and cognitive dysfunction.

Patients with Organ Failure

In patients with epilepsy and chronic kidney disease, dosages of levetiracetam, gabapentin, and pregabalin must be reduced because decreased clearance can lead to toxicity. Phenytoin is highly albumin bound; dosage should be reduced, and free (unbound) levels should be monitored. Gabapentin and pregabalin can cause encephalopathy and nonepileptic myoclonus, thus mimicking seizures. Valproic acid is typically avoided in patients with hepatic insufficiency. Because topiramate and zonisamide can cause acidosis and nephrolithiasis, they also should be avoided in patients with a predisposition to these disorders.

Posttraumatic Epilepsy

AEDs are prophylactically given during the first week after severe head trauma (loss of consciousness > 12-24 hours, intracranial hemorrhage, depressed skull fracture, or brain contusion) to prevent acute seizure complications (hemorrhage, edema, or elevated intracranial pressure). As with acute stroke, such treatment does not reduce the risk of developing epilepsy later, and prophylaxis beyond 1 week is not recommended.

A single unprovoked seizure that occurs more than 1 month after a stroke or significant head trauma has a high enough recurrence risk to be considered epilepsy and requires treatment. Patients with a history of moderate or severe head trauma (skull fracture, penetrating head injury, or loss of consciousness > 30 minutes) are at increased risk of epilepsy.

Returning combat veterans who develop seizures require careful evaluation, often including video EEG monitoring. Many have had head trauma and are at increased risk for epilepsy, but many also have posttraumatic stress disorder and may have PNES. Assuming a diagnosis of epilepsy and empirically treating the patient can be detrimental, especially because veterans tend to have a delay in the diagnosis of PNES compared with the general population.

Women with Epilepsy

Women with epilepsy may experience catamenial seizures (related to menstrual cycle), which may occur around menstruation or ovulation or because of an inadequate luteal phase. Some studies suggest adding progestin-containing oral contraceptives or acetazolamide to the AED regimen, but oophorectomy is not recommended to improve seizure control.

Reproductive Issues

Findings from various studies are contradictory about whether women with epilepsy have decreased fertility rates. Valproic acid, however, is associated with anovulation and polycystic ovary syndrome.

Pregnancy and Nursing

Most women with epilepsy have normal, healthy children. The rate of major congenital malformations (MCMs) in untreated women with epilepsy is likely similar to that of the general population. All women with epilepsy who are of childbearing age and are taking AEDs should receive preconception counseling and folate supplementation. Women with epilepsy who take AEDs are unlikely to have an increased risk of cesarean section, late-pregnancy bleeding, or premature delivery, unless they smoke; however, they may be at increased risk of having a newborn who is small for gestational age. The best predictor of seizure control during pregnancy is seizure frequency in the previous 9 to 12 months (especially for patients who have been seizure free).

In women with epilepsy who are of child-bearing age, levetiracetam and lamotrigine have minimal evidence of teratogenicity and are the preferred treatment options. Select patients, however, may need to continue potentially teratogenic medications, such as valproic acid, especially if seizures cannot be otherwise controlled. Discovery of pregnancy alone is not a sufficient reason to stop AEDs in women with epilepsy whose disease is well controlled. Women with epilepsy must balance risk of teratogenicity with risk of uncontrolled seizures, particularly GTCS, which can result in fetal anoxia and death.

Valproic acid, phenobarbital, and phenytoin are associated with MCMs and lower IQ in offspring; these drugs should be avoided if possible in pregnant women with epilepsy. Topiramate, carbamazepine, and AED polypharmacy also should also be avoided because of increased MCM risk. Valproic acid is associated with neural tube defects, and topiramate with cleft lip and palate.

Serum levels of lamotrigine, oxcarbazepine, and levetiracetam are known to decrease significantly during pregnancy. For lamotrigine, a dose escalation of approximately 50% is needed to maintain therapeutic levels and prevent seizures; levels should be followed at least monthly during pregnancy. Once delivery occurs, the lamotrigine dose should be rapidly decreased to avoid a sudden increase in serum levels, which would increase toxicity and risk of Stevens-Johnson syndrome.

Because the benefits of breastfeeding most often outweigh the risks, breastfeeding is recommended in most women with epilepsy who take AEDs. Sedation of the infant is a potential complication, but AED exposure through breast milk is usually minimal and probably less than that in utero.

Contraception

Enzyme-inducing AEDs (see Table 22) increase the metabolism of oral contraceptives, which decreases their effectiveness and thus increases chances of pregnancy occurring (while taking potentially teratogenic medications). Alternate methods of contraception, such as intrauterine devices or barrier methods, are thus recommended. Oral contraceptives also increase lamotrigine metabolism, which necessitates dosage increases.

Status Epilepticus

Not all seizures require emergent treatment. Most GTCS will cease spontaneously within 2 to 3 minutes, and, if the patient has stopped shaking, treatment is not necessarily indicated. Treatment also differs depending on the type of status epilepticus. Convulsive status epilepticus (CSE) is analogous to ventricular fibrillation (that is, a true medical emergency). Nonconvulsive status epilepticus (NCSE) is analogous to atrial fibrillation with or without rapid ventricular response (management varies with symptom severity). The cause of a seizure most often determines the outcome; thus, evaluation for serious causes (meningitis, intracranial hemorrhage) must occur emergently and in parallel with treatment.

Convulsive Status Epilepticus

CSE is defined as a generalized tonic-clonic seizure lasting more than 5 minutes, or two GTCS occurring within 5 minutes of each other without a return to baseline mental status. CSE is diagnosed clinically and presents as continuous generalized clonic jerking of the entire body. Unless PNES is strongly suspected, empiric therapy is indicated without awaiting results of EEG, imaging, serum studies, or lumbar puncture because a longer duration of CSE is strongly linked to worse outcomes.

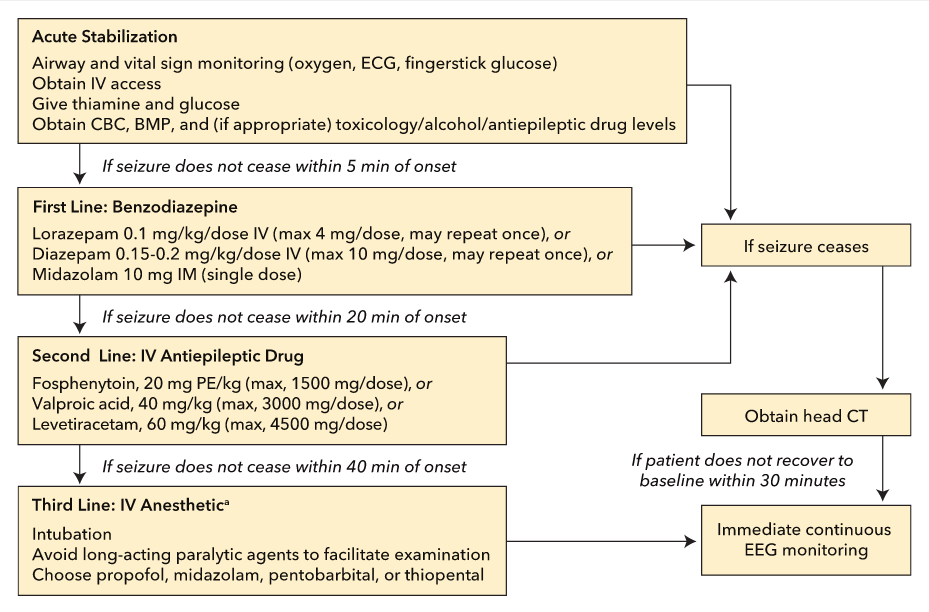

Securing the airway and obtaining intravenous (IV) access are the first steps in CSE management (Figure 9). If point-of-care glucose testing is not available, thiamine should be given, followed by IV glucose. First-line treatment is IV lorazepam, IV diazepam, or intramuscular midazolam. If IV access is not available, diazepam may be given rectally or intramuscularly, although absorption is erratic; intranasal and buccal midazolam also are available in some centers. Fear of respiratory depression should not limit treatment; there is clear evidence that respiratory depression is less common when CSE is treated with benzodiazepines than with placebo.

Management guidelines for convulsive status epilepticus. BMP = basic metabolic panel; CBC = complete blood count; ECG = electrocardiology; EEG = electroencephalographic; IM = intramuscularly; IV = intravenous(ly); max = maximum; PE = phenytoin equivalents.

Management guidelines for convulsive status epilepticus. BMP = basic metabolic panel; CBC = complete blood count; ECG = electrocardiology; EEG = electroencephalographic; IM = intramuscularly; IV = intravenous(ly); max = maximum; PE = phenytoin equivalents.

In a patient who is not already on AEDs, benzodiazepines should be followed by an IV AED to avoid seizure recurrence when the initial treatment wears off. Fosphenytoin (Cerebyx) is preferred over phenytoin (Dilantin) because it can be infused more rapidly and has a lower incidence of skin necrosis (such as purple glove syndrome due to drug extravasation). However, both fosphenytoin and phenytoin can cause acute bradycardia and hypotension. Alternative second-line therapies include IV valproic acid (Depakote) (especially in generalized epilepsy) or IV levetiracetam (Keppra). There is not enough evidence to support the use of lacosamide as a standard treatment in CSE.

Simultaneously with treatment, emergent evaluation for the cause of CSE should be underway, including provoking factors and triggers. A complete blood count, comprehensive metabolic profile, and evaluation for infection (with urinalysis, chest radiography, and lumbar puncture) should be considered. Head CT is usually indicated before lumbar puncture, but no test should delay the administration of antibiotics if meningitis is suspected.

If convulsions stop but the patient does not either improve within 10 minutes or return to baseline within 30 minutes, immediate continuous EEG is required to diagnose NCSE. NCSE after CSE is still a medical emergency and should be treated aggressively. If convulsive seizure activity does not cease, intubation is typically required, and third-line therapy with IV anesthesia should be initiated. IV anesthesia carries considerable risk, including prolonged ICU hospitalization and associated morbidity (infection, deep venous thrombosis) because patients are typically placed in a drug-induced coma for 24 to 48 hours. Therefore, concomitant continuous EEG monitoring is mandatory. Infusion of propofol, midazolam, or pentobarbital may be considered for NCSE that follows CSE. Hypotension is most common with pentobarbital, which may accumulate in tissues and require many days for clearance. Midazolam is least likely to cause hypotension but often leads to tolerance and tachyphylaxis. Because risk is determined by dose and duration of drug therapy, treatment should be limited to less than 48 hours.

Nonconvulsive Status Epilepticus

NCSE refers to episodes of electrical seizure activity without clinically evident seizure activity. It should be suspected when a patient, particularly a critically ill patient, has altered mental status with an unclear cause. NCSE may occur in as many as 48% (more typically, 15% to 25%) of patients with encephalopathy who are in the ICU. Certain situations should prompt consideration of NCSE and immediate continuous EEG monitoring (see Table 18). Although EEG is required for diagnosis of NCSE, appropriate clinical correlation of EEG findings is necessary to confirm NCSE and guide treatment. EEG of a few hours duration typically is inadequate because many patients experience intermittent rather than continuous seizures. At least 24 hours of monitoring is recommended in noncomatose patients, and at least 48 hours is recommended in comatose patients.

NCSE that does not occur directly after GTCS or CSE may not necessarily carry as high a risk to the patient as NCSE that follows these seizure types, but evidence is lacking. Treatment is based on clinical examination and not on EEG alone. If the patient is not comatose, initiating aggressive therapy with intubation and an IV anesthetic–induced coma is usually avoided because risks may outweigh benefits. Outcome is typically based more on cause and less on severity or duration of seizures.

Absence status epilepticus is a form of NCSE that typically occurs in patients with a history of generalized epilepsy but sometimes is seen in healthy older patients. Patients with this condition have days to weeks of mild confusion, despite being able to speak and walk (“walking wounded”); EEG confirms the presence of continuous generalized spike-and-wave discharges. Prognosis is excellent because treatment with IV benzodiazepines, valproic acid, or levetiracetam will usually resolve the problem, even in patients with days or weeks of seizing.